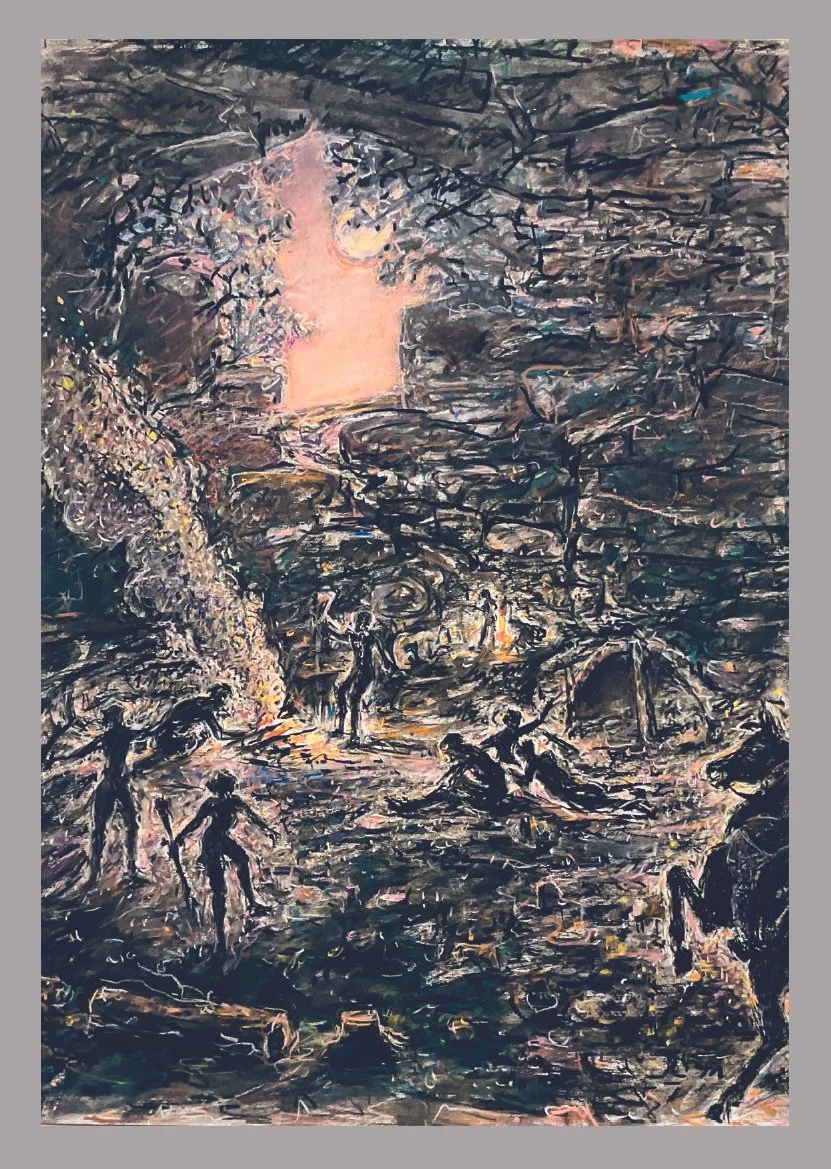

Dark Matter (2025)

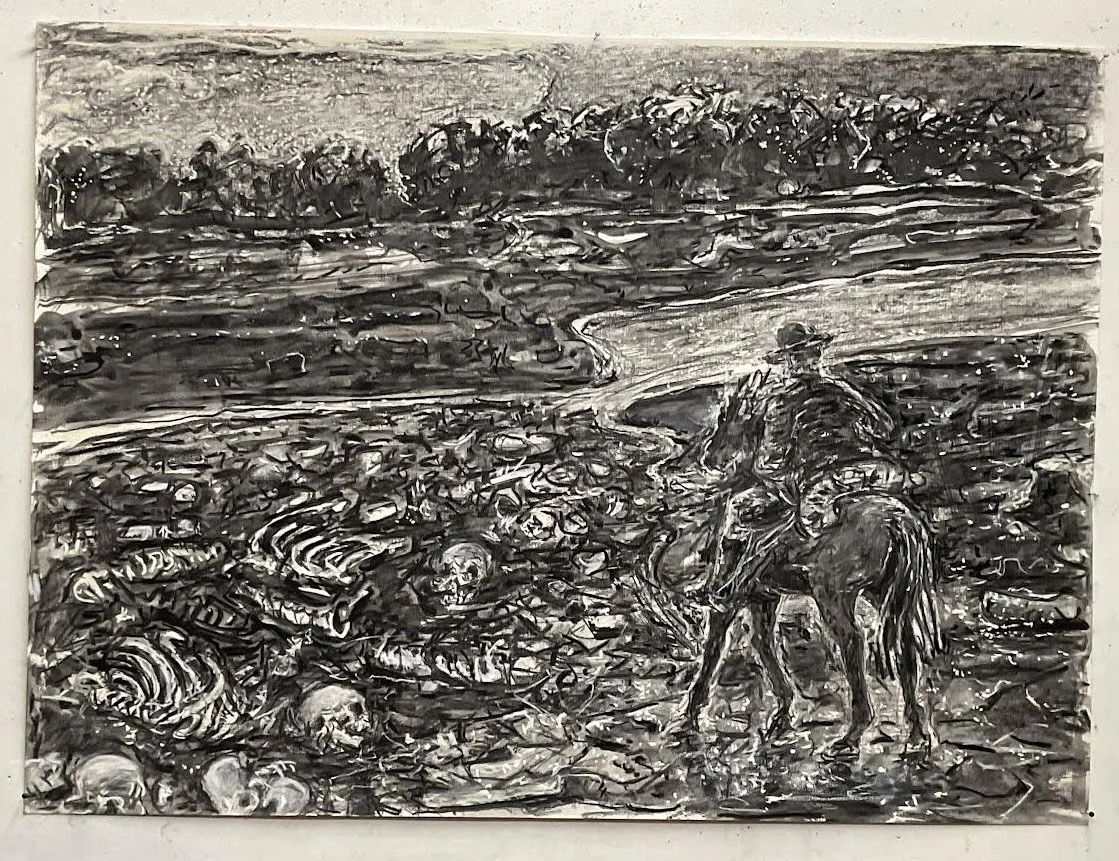

The Voice Referendum was the stimulus for this body of work. I was saddened that there wasn’t a greater knowledge about our history as a country including the deep cultural practices, ancient knowledge and way of life of the first people of Australia. In particular, the Referendum provoked me to attempt to address ‘the great forgetting’, the violent history of colonisation including the massacre of at least 10,000 Indigenous people [1] and perhaps as many as 60,000 [2].

The great forgetting is one of the most important aspects of Australian intellectual and cultural life during the first sixty years of the 20th century. [3]

I am not indigenous and grew up near Bathurst, where there were some terrible massacres. I never learned about these at school. Over the past few years, I have read widely about the Indigenous massacres and about the often cruel and barbaric methods used such as poisonings [4] and trophy collecting.[5]

The lack of national understanding about the massacres is reflected in our art history. While there is rightly a strong interest in Indigenous art and also a body of colonial painting, I think the main painting in this exhibition might be the first large History Painting to attempt this subject.

So how are we to find a place for the women and men of the First Nations who died fighting for country kin and customs? When will Australia find appropriate ways to illustrate that it recognises, values and respects their sacrifice?[6]

I have struggled with the ethics of portraying this subject – can I as an Anglo-Australian reflect on this dark matter? However, I have come to believe that the massacres are also the history of non-Indigenous Australians. Unless we come to own this history, we will never be a cohesive and fully mature nation. These works are therefore intended to help inform non-indigenous Australians about their history, painful as this might be.

I asked Lyndall Ryan …which Indigenous scholars I should read and [she said]:

“But they don’t work on the frontier wars the topic is whitefella business”. An Indigenous colleague I have known for many years put it this way “You mob wrote down the colonial records, the diaries and newspapers. You do the work. You tell that story. It’s your story”.[7]

[1] Ryan Lyndall "Colonial frontier massacres in Central and Eastern Australia, 1788–1930: Statistics". University of Newcastle (Australia). Retrieved 16 October 2024

[2] Reynolds, Henry Truth Telling Sydney, NSW : NewSouth Publishing, 2021 pp186

[3] Ibid Reynolds Henry pp163

[4] Bottoms Timothy Conspiracy of silence Crows Nest, NSW : Allen & Unwin, 2013 eg pp86-88

[5] Ibid Bottoms Timothy pp161

[6] Ibid Reynolds Henry pp243

[7] Marr David Killing for country Collingwood, Vic. : Black Inc., 2023 pp 409

Responding to Dark Matter - Ross McLean

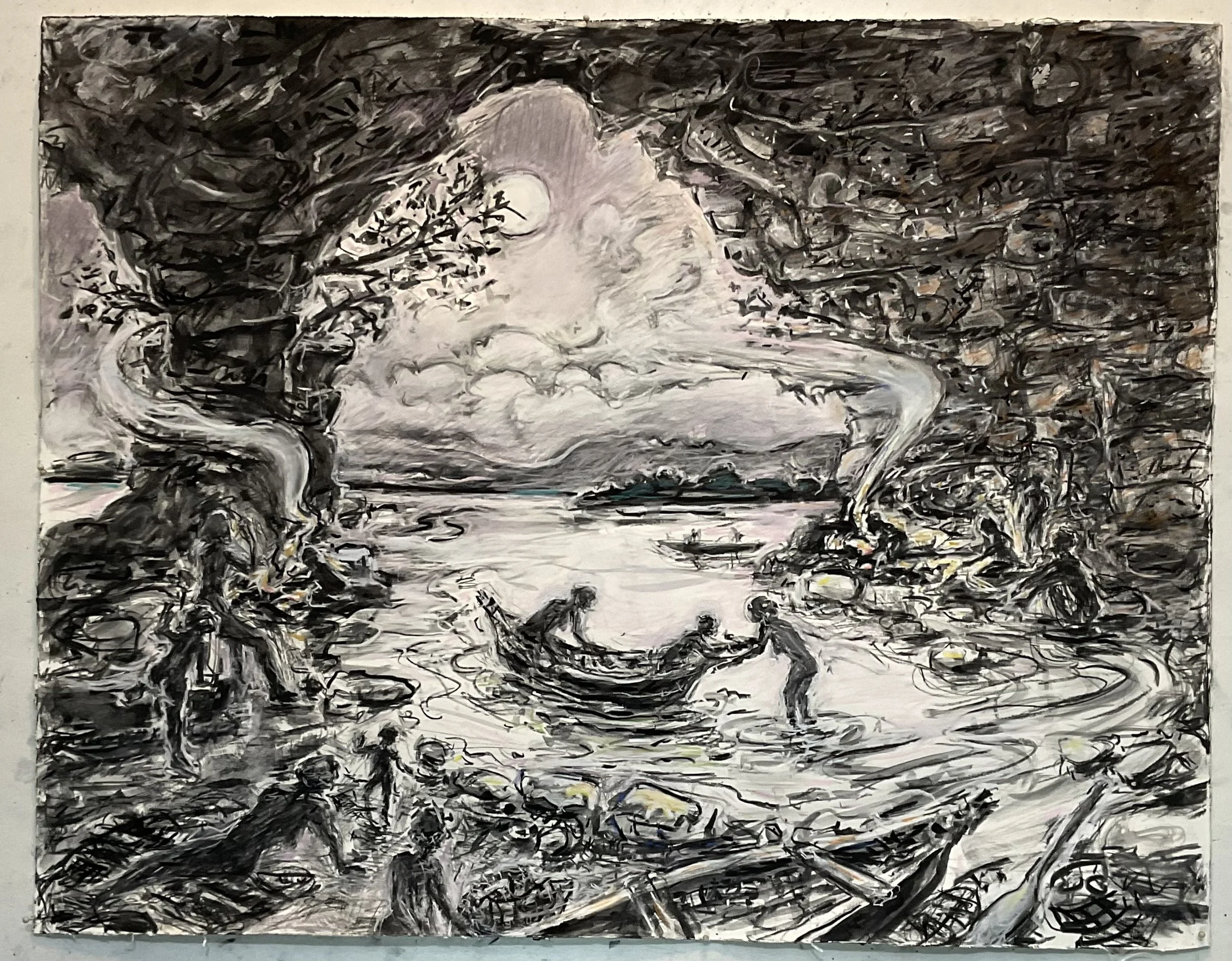

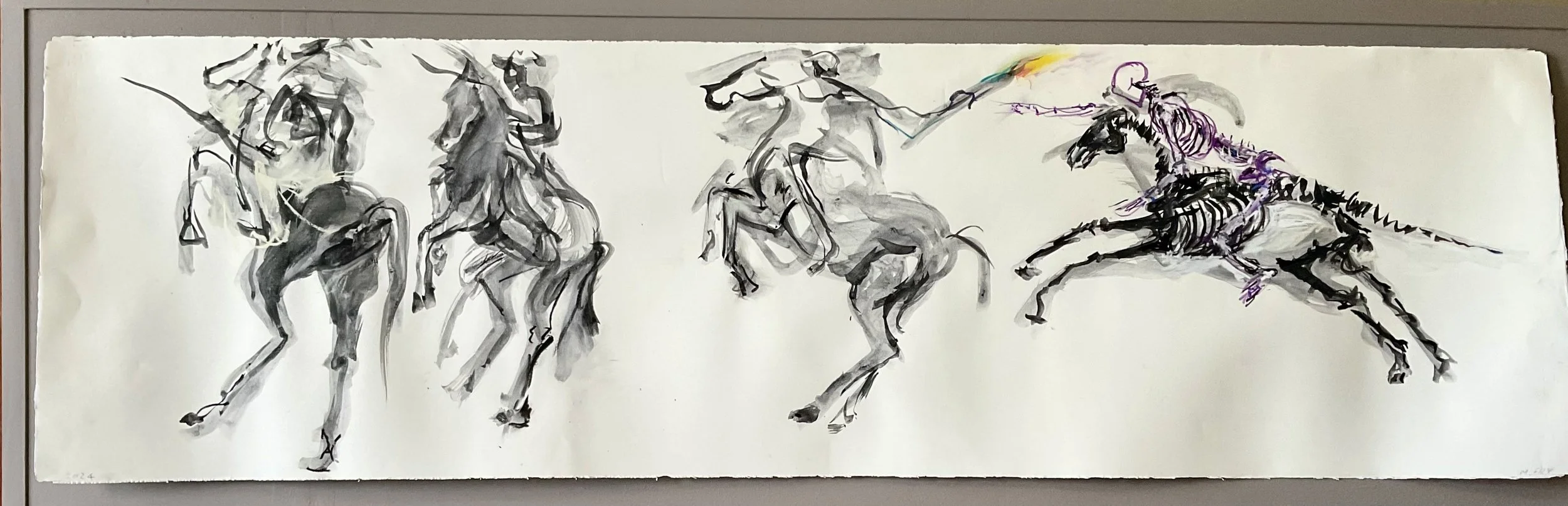

1. I see that it is a history painting. The scale and style. The subject. Colonial Australian history: the indigenous camp and armed raiders on horseback. Frontier conflict. A killing raid; a massacre if it involved planned killings of many undefended people as was most often the case. There were many hundreds of such events across a century or so. The painting is not specific as to which killing raid or where and when it took place. It is an archetype of such events, many of which took place at night or dawn.

Henry Reynolds, David Marr and many others have argued that these events were central to the conquest of Australia. If we are a conquered country, these killing raids (and those by indigenous fighters against settlers and squatters) are central to “how Australia was won” as Marr puts it. Conquered place by place. They are foundation stories. And yet paintings of these events have never illustrated our history books or hung in our museums or galleries. In the very period when history painting was at its peak our history paintings were of settler Australians fighting in a foreign (e.g. Boer) war, not in the frontier conflicts which, once concluded, we wanted to forget. They were not consistent with a story of heroic settlers building a new egalitarian nation which until the last 40 years or so was the story our historians wanted to tell.

Dark Matter is not a polemic painting. It does not depict specific acts of brutality. The action is about to unfold. What happened before, next and after is not referenced and we do not get the artist’s viewpoint on the event (cf. a book or television documentary or film). But Dark Matter does have a political dimension. A history painting centres an event as being historically significant. Takes it to be part of the audience’s shared knowledge of history, as the massacres have increasingly come to be. Not isolated or small events that have been forgotten and lost in time. Dark Matters asks us (non-indigenous Australians) to acknowledge and accept that we are looking at a working of a significant story (like our convict story) in our history. A story to reflect on, to grapple with, to apply our imagination to in an effort to understand its significance at the time and over time.

2. What can a very large realist painting contribute in 2025 to telling the story of events that are covered in detailed academic history books, in family histories like Killing for Country, and multi-episode television documentaries? By comparison, a single image certainly has limits in the amount of knowledge it can convey.

Of course, a good painting can be enjoyed for its qualities as a painting whatever the subject (or non-subject). But a history painting is also about communicating a story that we know. It can do this quickly - we don’t need to read or watch for hours. In a short time it can stimulate curiosity, memory and imagination. It can conjure a place and time, the world of the events. It can engage the senses in a different, direct and immediate way and then keep them engaged.

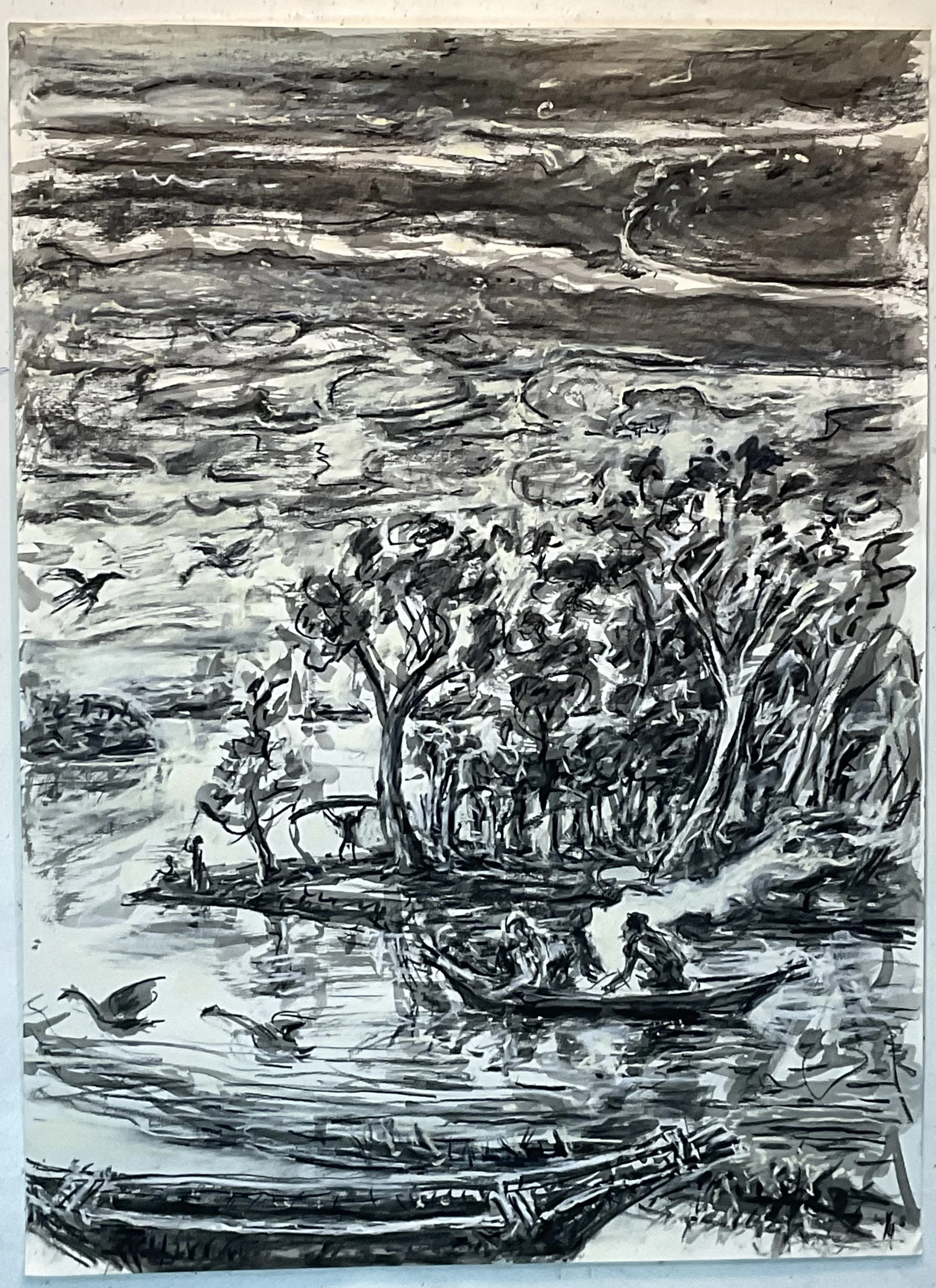

In Dark Matter the sense of night, of vulnerability, and of isolation is very strong. The camp is in a dark corner, out of reach of any authority, protector or watching public. The enormous starlit sky and expanse of moonlit water illuminate the darkness surrounding the camp and emphasise the exposed fragility of the families around the fire. Our memories and imagination can put us in this world, we are not distracted by the need to read on, or keep viewing, to see where events lead or how the story ends. We have to feel our way into the story of the before and after of the events depicted in the image.

This strong sense of the still, quiet life of the secluded camp at night helps us better feel or imagine the oncoming thunderous noise, speed and intimidating power of the raiding party as it storms in, armed men huge on horseback and intent on killing. The overwhelming shock and terror.

All these disparities or dualities (old world/new; darkness/light; stillness/speed; quiet/ noise; peace/violence) co-exist in a single image and create a context for the event, an atmosphere that helps us better sense the sudden enormity of the exploding terror. A terror which co-exists and is contrasted with the wonder and immensity of an infinite unchanging night sky, and of an ancient landscape softly lit by the moon and Milky Way.

3. Dark Matter is both an echo of colonial history and of an earlier history painting, Adam Elsheimer’s 1609 Flight into Egypt. There the flight is an escape from Herrod’s henchmen, a successful escape from a massacre (of all less than 2 year old boys) to the refuge of shepherds by a fire in a cave. Elsheimer’s composition is both closely followed and inverted (the firelit camp/cave is a killing field not a refuge) to tell a very different foundation story.

In the biblical story the high domed sky still contrasts with the earthly (to which one reviewer poetically said it was “buttoned” by the reflection of the moon in the water) but also carries the suggestion of omnipotent oversight, of Jesus’ family being guided by the (divine) light to safety. Whereas in Dark Matter the boundless sky seems a timeless, disinterested witness. It is remote from the time and place of the terror being enacted in a dark corner on earth.

More recently Elsheimer’s sky has been argued by the critic Julian Bell (in his book on Elsheimer, “Natural Light”) to also have a more metaphysical, less religious role in the painting. It illuminates the place of humans in the cosmos, and their dislocation from the natural world. We are in it but restless, in contrast to the stillness of the water. In Dark Matter the disjuncture is even more pronounced. The restlessness is at a crescendo, the brutal human agendas exposed.

The night sky has always been a place of mystery for humans. In Elsheimer’s time (that of Galileo) scientists were just beginning to learn the basics. His infinite sky was probably the first (in western art) to be based on close observation. Today we know much more but it still remains largely a mystery - dark matter and dark energy being some 95% of the universe but we know little about either.

In Dark Matter the Elsheimer sky has been altered to reflect the events depicted having taken place in Australia. But it is still painted as a place of wonder, a catalyst for the imagination, a locus for humans to home gods and ancestors. It is the sky, Bell writes, that gives Elsheimer’s painting its “poetic lift off, up into the wonderful and the strange”. A deliberate artistic choice to have it dominate the painting and the story below, and to depict it with such life and detail. Dark Matters adopts these choices and again this both amplifies the earthbound story it depicts and opens the painting up to wider engagement.

4. In “Why Weren’t We Told?” (1999) Henry Reynolds concluded that “knowing brings burdens which can be shirked by those living in ignorance. With knowledge the question is no longer what we know but what we are now to do, and that is a much harder matter to deal with. It will continue to perplex us for many years to come”. This remains the case. The Uluru Statement from the Heart and the Voice Referendum were attempted steps in one direction towards answers. There will be other steps, maybe other directions.

On a large canvas Dark Matters makes bold what we know and will not now be allowed to forget. It does this in a uniquely painterly way - it creates an atmosphere, mystery and world which invites us to linger and imagine, to engage with and consider/care about what happened and the consequences. Including the question of what we are now to do.

Ross McLean

March 2025